Nat Baldwin - People Changes

The fifth in a string of solo albums over the past few years, the bassist of Dirty Projectors and contributor on such albums as Vampire Weekend's Contra and Department of Eagle's In Ear Park, Nat Baldwin has undeniably been a busy boy. Whilst some of his previous 'solo' work has found him in the company of a fair few others, People Changes presents Baldwin single-handedly crafting an album of poignancy and flair.

Album opener and Arthur Russell cover 'A Little Lost' begins with a delightful bass scratching, the opening lyrics "I'm a little lost without you/and that could be an understatement," are as pleasant and heart-warming as the double bass accompaniment. The simplicity of the song, like the Russell version, is where the charm truly lies, with Baldwin's crescendo floating elegantly above the backbone of the double bass. Throughout the album we come to find that like the opener, the Baldwin's favoured double bass really is the backbone of the whole operation. Recorded and written in true Bon Iver style, within the confines of a cabin in rural Maine, much like For Emma, Forever, the album is bursting with ambiance, under such minimal circumstances.

As the album unfolds we find that it is not all four-strings and Baldwin, as the second track 'Weights' begins with a kind of weird plughole noise before developing into a fluttering wind section. The return of the strings and Baldwin's voice marks the turn from gutter to glory as the song progresses. Likewise on 'Lifted,' Baldwin flexes his musical muscles by incorporating percussion, saxophone and guitar in what serves as the album's most freeform and jazzy point. Having worked under jazz guru Anthony Braxton in the past, Baldwin is no stranger to the chaos of freeform jazz and he utilises this chaos to juxtapose the calmness of his voice and double bass admirably.

With these tracks in particular serving as the key moments of the album, Nat does tread into unsavoury waters at times. This is most apparent on the instrumental 'What Is There' in which he attempts to push his double bass to its limits, an experimental procedure that the instrument seems to suffer painfully through. As revealed throughout the album, the double bass is an instrument of pleasure and pain with highs at the bookends of the album and lows on the instrumental and the end of 'Real Fakes.' At seven tracks long it is hard to imagine from the quaint opening that the album is capable of such unsavoury moments, but aside from these blemishes it is a thoroughly delightful album to behold. The lows may be rock bottom, but the highs are truly a sight to behold.

6.5/10

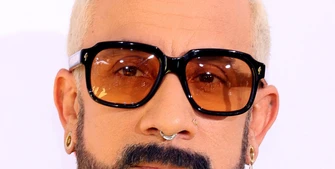

Joe Wilde